OVERVIEW OF THE PRACTICE OF ARCHITECTURE IN EDMONTON 1930 ‐ 1969

David Murray / Marianne Fedori

August, 2007

In the 1930s Edmonton architects, like many of their contemporaries across Canada, were starting to embrace the theories and practices of Modernism. They were experimenting with Art Deco and its offspring, the Moderne (Streamline) Style and eventually the International Style. Early commissions were modest in scale: schools, churches and some houses. The acceptance of Modernism and the post‐war building boom led to a maturation of the architectural community and set the foundation for a culture of modernist expression. In this period, many sophisticated Modern buildings were constructed, culminating with the internationally acclaimed Housing Union Building (HUB) at the University of Alberta in the late 1960s.

University of Alberta Architecture Program

In 1913 Cecil Burgess arrived in Alberta to become an architectural consultant for the University of Alberta on the recommendation of Canada’s leading architect of the time, Montreal’s Percy Nobbs. Within a few months of his arrival Burgess was appointed Professor of Architecture and University Architect. He taught students, many of whom were enrolled in Engineering or Science programs, the history of architecture, architectural design and drafting. Although there was no formal degree in Architecture until the 1930s, students who graduated from this program applied for professional registration through the Alberta Associations of Architects. The testing and regulation of their qualifications was handled by Professor Burgess. In 1931, an architectural program was formalized at the University of Alberta with a Bachelor of Science in Architecture.

Little is known about the school and its curriculum. Trevor Boddy in Modern Architecture in Alberta points out that the small size and short life of the U of A program “were no indication of the quality of graduates it produced.” Burgess was very critical of the values of Modernism. He wrote numerous articles for the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada Journal on this subject and frequently expressed his dislike for the functional form of Modernism in his regular monthly submission. Burgess believed in and employed the methods of the Beaux‐Arts tradition and emphasized a practical approach to design. Despite his reluctance to embrace Modernism, Burgess’ students became significant players in the practice of Modern architecture in Alberta, especially after World War II. U of A graduates included:

| 1932 | John Ulric Rule and Maxwell Dewar |

| 1932 | George Heath MacDonald |

| 1936 | John Alexander Cawston, Lloyd George MacDonald, John Stevenson, Paul Temple Bruno, Edward Yee Wing, and Gordon Kenneth Wynn |

| 1937 | Victor Meech and Margaret Dell Buchanan |

| 1938 | Ross Meredith Stanley |

| 1939 | Margaret Findley, George Willington Lord, Gordon Aberdeen, T.V. Throth, Peter Leitch Rule and Jean Louise Embery Walbridge |

| 1940 | Lorne Burkell and Neil McKernan |

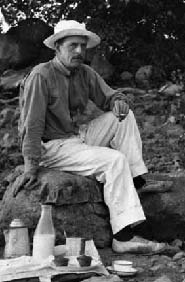

Left to right: John Rule, Gordon Wynn, Peter Rule (50 Years in Architecture, HIP Architects), George Lord (Nancy Lord), Neil McKernan (The McKernan Family)

In 1940, Cecil Burgess retired from the University of Alberta and, as a result, the School of Architecture closed. Burgess continued to act as Alberta’s editorial representative to the RAIC Journal. He remained very skeptical of the Modern movement in Canada but started to bring forward his interest in new concepts of town planning. Burgess believed that architects needed to understand proper planning techniques to be truly successful. An Interim Report of the Edmonton Planning Commission published in 1944, spearheaded by Burgess, was reprinted in the RAIC Journal in 1945. The plan specified a layout for Edmonton’s Hudson’s Bay Company Reserve and adjoining areas. Burgess modeled his planning concepts in part, on Eliel Saarinen’s The City ‐ It’s Growth, It’s Decay, It’s Future.

Modernism Takes Hold in Edmonton

Edmonton’s citizens and builders were keenly interested in new Modern styles. In 1936, the “The Home of Tomorrow”, now located at 1 St. George’s Crescent, was built through the sponsorship of the Edmonton Bulletin as a way to give homeowners a glimpse of modern construction, form and decoration. Built by local contractor Ernest Litchfield from the award‐winning plans of a competition sponsored by the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, the home was considered the last word in a modern low‐cost Canadian residence and was Edmonton’s first model home. This public display of Modern architecture helped to set the stage for architectural commissions that soon followed.

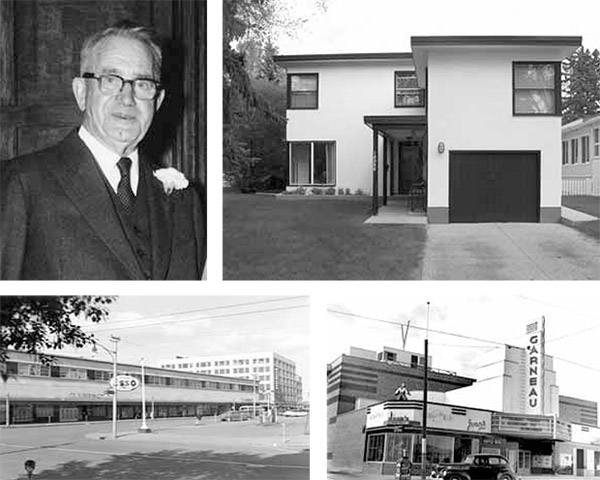

Counter clockwise from top left: William Blakey (The Blakey Family), Eatons Store (Edmonton Archives EA-10-1797), Garneau Theatre (Provincial Archives of Alberta A6885), William Blakey Residence (David Murray)

Some architects from the earlier part of the 20th century continued to practice through the 1930s and into the post‐war period, most shedding the Beaux Arts design tradition in the 1930s. Brothers William Blakey and Richard Blakey, having practiced since before WWI, introduced Modernism as early as 1935 in their residential commissions. In 1938 William Blakey was hired as the local architect by Manitoba architects, Northwood and Chivers, when the Eaton’s showcase Moderne Style store was designed for downtown Edmonton. In the same year he designed St. John’s Separate School using Streamline Moderne Style influences and in 1940, the Garneau Theatre, which emulated the International Style. In 1946 Blakey built a distinctive home for himself in Glenora following the Modern practice of flat roofs, corner windows and no basement. In the same year, his strongest competitor, George Heath MacDonald, also a leading architect, designed a modern home for Justice Hyndman right across the alley from Blakey’s residence. The homes were considered architectural curiosities on the edge of Edmonton’s expanding suburban cityscape.

Lefet to right: Varscona Theatre (Provincial Archives of Alberta PA2544.5), Blatchford Field Control Tower During WW 2 (Provincial Archives of Alberta BL7144.2)

In 1938, John and Peter Rule, with Gordon Wynn, formed the architectural practice Rule Wynn and Rule. The early years of their practice included the design of modern movie houses. The now demolished 1940 Varscona Theatre was Edmonton’s premier example of the Moderne Streamline Style. In the late 1930s, architects still had trouble gaining commissions due to the slow economy. Rule Wynn and Rule, for example, accepted smaller commissions including the Foster & McGarvey Funeral Home and the Bonnyville Convent, in revival styles, and later the neo‐Georgian Rutherford Library at the U of A. These commissions responded to their clients’ conservative interests. Such was the case with Glenora School for the Edmonton Public School Board in 1940 (Tudor Cottage Style), which was specifically designed to reflect the earlier country garden residences of Old Glenora. Many of these early commissions were not reflective of their emerging interest in Modernism.

World War II

During the 1940s many young architects left for Europe to serve in World War II. Older architects served the war‐time situation by lending their expertise to the Federal Government. William Blakey returned to Ottawa (he had worked in Ottawa during World War I) to work with the Standards and Measurements Branch. John Rule and Gordon Wynn joined the Navy and the Air Force, respectively. Peter Rule Sr., John’s father, came out of retirement to watch over the Rule Wynn Rule partnership. In 1941, Peter Rule Sr. was granted a special certificate to practice by the Alberta Association of Architects. There was enough work to hire fellow architecture students Mary Imrie and Doris Newland.

City Architect John Martland (in office from 1926 to 1944) dealt with a critical housing shortage during the war. Martland chaired a special taskforce that was established to address federal housing schemes. In 1937 several hundred houses were constructed based on Martland’s designs in Edmonton’s first municipal housing program. He aided in the design of a number of hangars at Edmonton Municipal Airport and designed the Municipal Airport Administrative Building, a significant modern terminal, before he retired from his position in 1944 and was replaced by Maxwell Dewar.

After the War

The post‐war building boom created an opportune time for architects to enter the field. It was a period of energized growth across the country and particularly in Edmonton following the oil discovery in Leduc in 1947, which caused a dramatic and significant shift in Edmonton’s economy. The development of the petrochemical industry also brought new basic and secondary industries. There was a great need to replace or fix existing infrastructures in cities and war‐time industries were converted to peace‐time applications. Architects who had been struggling for work before the war were now in high demand. Maxwell Dewar, City of Edmonton Architect, and also President of the Alberta Association of Architects in 1946 and 1947, reported that architects “must respond to the rising tempo of the times.” Dewar stated in his presidential address to the Alberta Association of Architects that the year 1946 “had been a strenuous one… that a great effort has been necessary to meet the demands of society for industrial, commercial, public and residential buildings.” Maxwell Dewar and those in his City Architect’s Office were challenged by the demands of urban expansion. Rising construction costs, material shortages, lack of skilled workers and labour unrest made it difficult to complete projects.

In 1946 the architectural draftsmen of Alberta organized themselves. The Alberta Association of Architects became the regulator of their examinations, thus exercising standardization of drafting practices. At this time, some draftsmen entered into the profession of architecture, including Douglas Campbell who completed his architectural studies by correspondence and worked in the City Architect’s Office until he went into private practice with Garth Fleet (Campbell and Fleet) in the early 1950s.

Several prairie‐born veterans, returning to Canada after the war, entered the University of Manitoba Department of Architecture, the largest school of architecture in Western Canada at the time. Formed in 1912, the University of Manitoba started a post‐graduate program in 1948 under the direction of Dean John Russell. The school emphasized a Modern approach to architecture, with architects trained as both planners and builders. Many of their graduates came to Edmonton to take advantage of the city’s booming economy, including: Roy Meiklejohn, H. Henderson, Leonard Klingbell, Eugene Olekshy, Jack Annett, Gordon Forbes, Bernie Wood, Jack Gardner and Kelly Stanley.

In 1947, Edmonton’s most celebrated female architects, Jean Wallbridge and Mary Irmie left for a six week tour of Europe to examine post‐war construction. They visited Poland, Czechoslovakia, Sweden, Denmark, Holland, Switzerland, Belgium and England. When they returned to their positions with the City Architects Office, The Edmonton Journal reported they had “fresh ideas and enthusiasms for their work in the architectural field.” Their trip was widely publicized and brought new attention to international trends in architecture.

The late 1940s was a time of extraordinary growth. The population of Edmonton doubled in the three years from 1945 to 1948. In a report in the January 1949 RAIC Journal, Gordon Wynn stated: “There is more opportunity in Edmonton than anywhere in Canada. The Architect will need to play a big part in the development of this area.”

One of the finest buildings from the 1940s is Victoria Composite High School, the first composite high school constructed in Edmonton. The first phase was designed by Maxwell Dewar as City Architect and opened in fall 1949, to be completed in 1951. This was quickly followed by an exemplary addition in 1953 by (W.W.) Butchart, Cawsey & Macdonald Architects and again followed by a Rule Wynn Rule designed addition in 1962. In 1951 the American School Publishing Corporation of New York awarded Maxwell Dewar one of five awards for the most outstanding schools built in Canada and the US. The Edmonton Journal reports that the judges said it showed a “thorough study of organization and detail” and made provision for “effective housing of a very comprehensive program”. In 1949 Dewar left the position of City Architect and entered into private practice to head up the Edmonton branch of the Calgary firm Stevenson Cawson Stevenson (later Dewar Stevenson Stanley), taking most of the City Architect’s Office staff with him. Mary Imrie and Jean Wallbridge resigned from their positions with the City’s Architect’s Office and took leave for an architectural tour of South America before opening their own practice. Robert Falconer Duke, the Assistant City Architect, took over Maxwell Dewar’s position. Noel Dant, an urban planner of great distinction from Britain and who studied in the U.S., was hired as Town Planner for the City in 1949.

An important practitioner after the war was Patrick Campbell‐Hope, born in 1908. Before World War II he had worked for William Blakey and later for G.H. MacDonald. His architectural training was gained practically, in architects’ offices, and he received a Diploma in Architecture through the RAIC Syllabus program. In 1947, Campbell‐Hope established his own office, which nourished young and upcoming architectural graduates (especially from Manitoba) who came to Edmonton for work including: Jack Gardner, Bernie Wood, Leonard Klingbell, Scotty Macintosh, Eugene Olekshy and George Chernenko. Campbell‐Hope’s accomplishments include: St. John’s (Ukrainian) Cathedral at 107 Street and 110 Avenue, the 1950 Land Titles Building at 100 Street and 102A Avenue, the 1950 Beth Israel Synagogue in Oliver, the 1954 Mill Creek Swimming Pool and the 1959 Strathearn United Church.

The architectural scene on North America’s Northwest coast was also beginning to influence the design of buildings in Edmonton. The University of British Columbia School of Architecture opened in 1946 and explored Modernism from the start. A number of architects, such as Don Bittorf and James B. Wensley were educated at west coast schools, the University of Washington in Seattle and UBC respectively. John Rule’s designs often incorporated West Coast Modernist Post and Beam Style design influences and the concern to connect with the landscape. In 1950, one of the most significant Edmonton houses of its time, designed for the Shandro family by Vancouver’s Fred Thornton Hollingsworth, a devotee of Frank Lloyd Wright, was constructed on University Avenue overlooking the river valley. It is the finest example of the Prairie Style in Edmonton. in 1954, architect George Lord, a graduate of the University of Alberta, designed a house on University Avenue for himself and wife Nancy that was also strongly influenced by the West Coast Post and Beam Style, perhaps as a result of his employment at Rule Wynn and Rule, where George was to become a partner in the 1960s.

Edmonton’s Architecture Comes of Age

Edmonton’s architects worked to meet the urgent need for urban expansion. Edmonton’s role as a distribution center for Northern Alberta and the Northwest Territories increased. To meet the rapid population growth, the City Architect’s Office under the direction of Robert Falconer Duke (1949 to mid‐1960s) and his assistant, William Telfer, designed many civic buildings, including utility buildings (incinerator, power plant, water filtration plant, fire halls), recreational structures (swimming pools, grandstands) and parks (playgrounds, baseball parks, public washrooms), which were all fine examples of the emerging interest in Modern design. The 1954 Borden Park Swimming Pool and Band Shell are excellent examples of the high quality of design work that was being produced by the City Architect’s Office.

The post‐1947 oil boom years brought a surge in public building, which was an important factor in the growth of Rule Wynn and Rule. Several early University of Alberta commissions went to them in 1948, including the University Hall and Rutherford Library, the last classically designed building on campus. The firm started its forty‐year association with the Royal Alexandra Hospital in 1950. The City’s expanding commercial activity was reflected in their designs for warehouses, plants and hospitals. In 1953, Rule Wynn and Rule designed the headquarters for Alberta Government Telephones (currently known as the Legislature Annex) adjacent to the Alberta Legislature. It was Edmonton’s first curtainwall building, just one year after Skidmore, Owings and Merrill unveiled their famous curtain wall Lever House project in New York. At the time it was described by some as ‘an offense against good taste’, demonstrating that not all Edmontonians were accepting of Modern forms and materials. Cecil Burgess also lamented the loss of classicism, and the acceptance of “steel steroids with more glass than walls” in his report to the RAIC.

Left to right: Salvation Army Hostel (David Murray), Strathcona Composite High School (David Murray)

An important practitioner in the 1940s and 1950s was Neil McKernan, one of the last graduates from Cecil Burgess’ U of A architecture program. McKernan was an accomplished designer as can be seen in his design for the 1950 Moderne influenced Beth Shalom Synagogue at 120 Street and Jasper Avenue and the International Style 1953 Salvation Army Hostel at 9611 ‐ 102 Avenue. He formed a partnership with Manitoba graduate Howard Bouey later in the 1950s. Their’s was a busy office producing, among other buildings, the refined 1957 Oliver Building for the Federal Government at 100 Avenue and 103 Street and the International Style 1958 Samuels residence at 13842 Ravine Drive for Joseph and Fannie Samuels.

Post‐war immigration brought a new group of architects to Edmonton from Belgium, Britain, Holland and Germany, including: Rudy Ascher, Duncan McCulloch, Freda and Dennis O’Connor, Kristjan Parn, Herbert (Bertie) Richards, Peter Hemingway, Bruno Templin, Clifford Larrington, Albert Dale, Victor Bathory and Julius Piffko. These architects gained work with established firms such as Rule Wynn and Rule and the Department of Public Works. They reinforced the practices and values of Modern architecture to which they had been exposed in Europe. The exploding population also required the construction of new schools. W.W. Butchart, the Edmonton Public School Board Architect from 1946 until the 1960s, oversaw the design of dozens of schools during his tenure, including the 1950 Westminster School and the 1959 Gold Bar Elementary School. His International Style designs, likely influenced by the buildings of John Parkin, Canada’s foremost modernist at the time, were the foundation for schools by other architects such as the 1954 Strathcona and Eastglen Composite High Schools both attributed to Rule Wynn and Rule. Butchart also designed a series of schools in Edmonton that were some of the finest buildings at a time when there was a fusion of the International and Moderne Styles.

The University of Alberta was also in a period of rapid expansion following the war. In the late 1950s and 1960s a number of landmark buildings were constructed that made the campus one of the best repositories of modern design in the city. The imposing University Hall had been designed by Rule Wynn and Rule in 1948. In 1952, St. Stephen’s College (separate from the University at the time) hired Dewar, Cawston and Stevenson to design a fine new building adjacent to the historic St. Stephen’s College. Many other buildings were constructed in these years, including the 1956 Administration Building, the 1951 Civil Engineering Building (by Rule Wynn and Rule) and the 1960 Chemistry and Physics Buildings that bordered and defined the central quadrangle, the latter three all designed by Alberta Public Works.

In 1953, Edmonton’s post‐war buildings came of age. The February issue of the RAIC Journal was devoted to contemporary Alberta architecture. Most of the buildings featured were in Edmonton: The Alberta Teacher’s Association Building (Stanley and Stanley), the house of J. Russell (Wallbridge and Irmie), St. Anne’s Chapel (Diamond, Dupuis, Desautels), the Provincial Tuberculosis Sanitarium (William L. Somerville, of the Alberta Department of Public Works), the Royal Trust Company Building (Dewar, Stevenson and Stanley Architects) and the Brown Building in Calgary (J.A. Cawston). The Premier of Alberta, Ernest Manning wrote the introduction to the RAIC Journal Showcase of Architecture in 1953. He commented: “Alberta is young and vigorous and receptive to new ideas provided they are progressive and wholesome. This province has demonstrated to the rest of Canada and to the world that her people are not afraid of experiment, adopting whatever is beneficial but not hesitating to abandon or reject the obviously profitless.”

By the mid‐1950s, Edmonton was on the verge of accepting the skyscraper. Such tall buildings included the 1957 Milner Building on 104 Street and the 1961 Bank of Montreal Building at 101 Street and Jasper Avenue, both designed by Rule Wynn and Rule. In 1957 the Bentall Block, a curtain wall clad box at 102 Street and 102 Avenue, was designed by C.T. Larrington. In 1957, James (Jock) Bell undertook his first large office commission, the Northwest Trust Building on Jasper Avenue mid‐block between 100 and 101 Streets.

By the end of the 1950s Edmonton architects were regularly working with large developers such as Oxford Properties. Oxford Properties was formed in 1960 by John and George Poole of Poole Construction. Poole Construction had been founded in 1922 by their father Ernest Poole, whose first Edmonton project was the Edmonton Public Library designed by G.H. MacDonald. John and George Poole, having relinquished day‐to‐day control of Poole Construction, were joined by a third partner Don Love from Dominion Securities. A development company under the name of POLO (short for Poole and Love) Developments was chartered for their first project, the 1959 Baker Clinic at 105 Street and 100 Avenue. A few years later they renamed themselves Oxford Investments and a formative development enterprise was born that would significantly affect the shape of Edmonton over the next few decades. Among their projects were the 1961 Bank of Montreal Building, the 1969 AGT and Imperial Oil Buildings (McCauley Plaza) and the 1968 Edmonton Centre, all designed by Rule Wynn Rule. Credits for the McCauley Plaza project also include Toronto’s Webb Zerafa Architects and for the Edmonton Centre Project, New York’s Skidmore Owings and Merrill.

Other important local developers from this period include Alldritt Developments, a multi‐family residential developer who responded to the demand for post‐war housing. This company often worked with architects Wallbridge and Imrie, and one of their finest projects is the North Glenora Patio Homes built on 135 Street at 110 Avenue in 1952. MacLab Enterprises also began business in this era, working with Wallbridge and Imrie on the 1955 Princess Elizabeth Apartments west of the 101 treet traffic circle on Princess Elizabeth Avenue. This large multi‐family project, although low cost, is one of the best of its kind in the city encompassing several city blocks with a well‐executed site plan to produce three large inner courtyards away from the busy streets. The building design also incorporated extensive use of brick in two colours that was unusual for its time.

The Banff Sessions

The inaugural Banff Session ‘56 was organized by the Architectural Association of Alberta and the Department of Extension at the University of Alberta to explore new architectural ideals and contemporary approaches. Thirty‐five architects met for a week at the Banff School of Fine Arts to hear the renowned modernist architect Richard Neutra speak, presided over by Howard Bouey, President of the Association. Neutra addressed the Association with a talk entitled “The Value of the Session of ’56 to Architects Here and Abroad”.

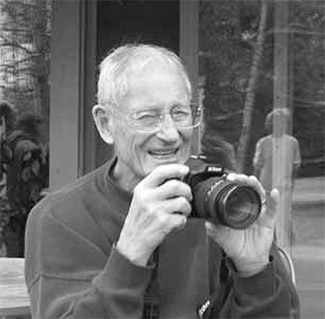

Howard Bouey greeting Richard Neutra and his wife at the Banff Session (Howard and Robert Bouey), Edmonton City Hall (Provincial Archives of Alberta WS122.2)

The following year, Session ’57 proceeded and was viewed as a milestone in Canadian architectural history by the participants. Richard Neutra returned and set the theme of the meeting: to have architects understand the “human organism for which we design.” All of Edmonton’s leading architects attended and Alfred Minsos wrote in a summary of the session that “Richard Neutra is no doubt one of the great personalities of contemporary architecture in the mid twentieth century.” Neutra and his wife, Dione, who also participated in the session, were toured through Alberta, and were very late for the gatherings as Neutra insisted on visiting the Hobemma Reserve in sub‐zero temperatures where he took many photographs of housing on the reserve.

Edmonton City Hall

The 1957 Edmonton City Hall was one of Canada’s first modernist city halls. It was designed by Dewar Stevenson Stanley. A 1954 Edmonton Journal article reported that Max Dewar was the partner in charge of the project, although he didn’t live to see its completion. Trevor Boddy, in Modern Architecture in Alberta writes that the City Hall was “a version of the International Style that refers to many periods and elements of buildings in the career of renowned French architect Le Corbusier. One of the first major downtown projects in Edmonton after World War II, the City Hall and its controversial “spaghetti tree” fountain captured the imagination of the bustling city as few have before or since.” City Hall incorporated luxurious materials, a Council Chamber on stilts, various types of window shades and a delightful undulating canopy over the rooftop cafeteria. It made Edmontonians feel they were very progressive. The building was replaced in 1992.

The 1950s End on a High Note

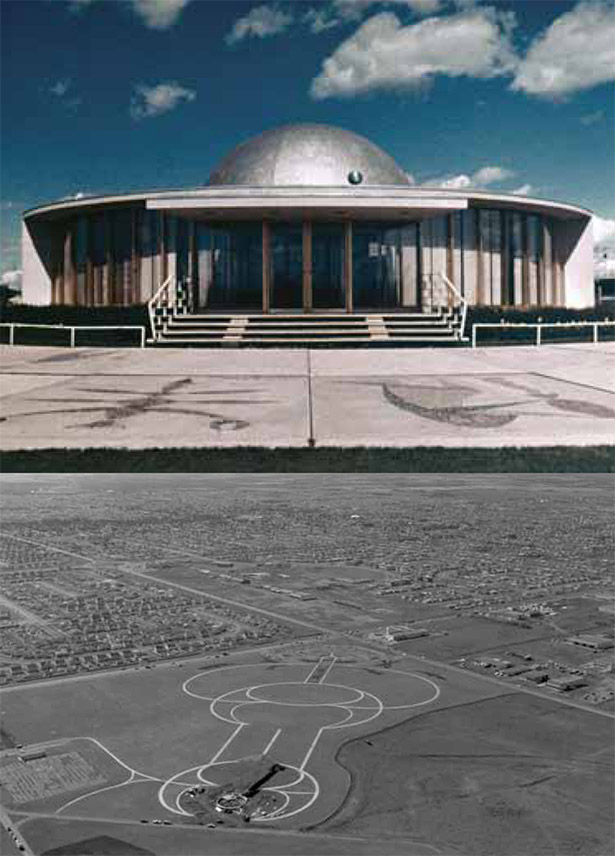

Edmonton City Council agreed to erect a permanent civic monument in the form of a landmark building to mark the July 21, 1959 visit of Queen Elizabeth II. This building was Canada’s first planetarium and the country’s only civic planetarium until the Dow Planetarium in Montreal opened in 1966. Called the Queen Elizabeth Planetarium, the building is an excellent and delightful example of Modern Expressionism, one of the most outstanding buildings of its time in Canada. It was designed by City architect, Robert Falconer Duke with the help of his assistant Walter Telfer in the City Architect’s Office.

Top to bottom: Edmonton Planetarium (Edmonton Archives EA-14-192), Aerial View of Coronation Park (Edmonton Archives EA-20-1038)

The 1960s ‐ A Brilliant Decade

The 1960s was a decade of unprecedented growth and creativity in Edmonton. Architects who took over older practices or who had formed their own practices in the 1950s were mature and in a position to produce some of the best post‐war buildings.

In 1960, Bernard (Bernie) Wood and Jack Gardner, both graduates from the University of Manitoba, left the office of Patrick Campbell-Hope to start their own practices. They shared an office and soon became partners. During this decade, their practice produced mainly rural schools and some houses. In 1961, Wood obtained the commission to design the General Veterinary Hospital at 11403 – 143 Street. This delightful and sophisticated little building is an example of modern Structural Expressionism that exposes, expresses and celebrates the building’s simple structural system.

James (Jock) Brock Bell and Duncan McCulloch formed their firm, Bell and McCulloch in 1954 and went on to become one of the most productive firms in the city. Jock Bell, son of the local hero James A. Bell, Superintendent of the Edmonton Air Harbour, was educated at the University of Manitoba, graduating in 1950. Duncan McCulloch was educated in Glasgow, Scotland and immigrated to Canada in the early 1950s. Their firm executed many significant commissions including the 1957 Christ Lutheran Church, the 1957 Northwest Trust Building at 10166 – 100 Street (now demolished), the 1960’s Edmonton General Hospital Additions and the 1969 Law Courts Building. Included in their work was the diminutive but sophisticated 1959 Administrative Office of the Edmonton Cemetery at 107 Avenue and 118 Street. They were also responsible for the Late Modern Style headquarters of the Separate School Board at 98 Avenue and 106 Street, which was constructed in 1960.

In 1961, John A. MacDonald, nephew of veteran practitioner George Heath MacDonald, designed two of the first concrete frame high rise apartment buildings to be constructed in Edmonton: Jasper House and Bristol Tower at 122 Street and Jasper Avenue. Calgary’s William G. Milne designed the TD Bank Building at the corner of 100 Street and Jasper Avenue, one of Edmonton’s first commercially-available curtain wall office buildings that used manufacturer’s stock aluminum window frame components. It was a progressive bank building design, embracing modern concepts, and stood in contrast to the earlier 1955 Imperial Bank of Canada building across the street, designed by Rule Wynn and Rule, which adhered to traditional classicism, albeit with an Art Deco flair. George Lord, who became a partner in Rule Wynn Forbes Lord in the early 1960s was responsible for designing a building for the Bank of Montreal, a 10-storey tower at the corner of 101 Street and Jasper Avenue that continued the trend toward Modernist bank tower design.

Left to right: Edmonton International Airport Exterior (Provincial Archives of Alberta PA531.3); Edmonton International Airport Interior (Provincial Archives of Alberta PA531.5)

The 1960s was an optimistic era that demanded more buildings with a progressive outlook. Air travel was growing and in 1961, the federal government put out a call for the design of a new International Airport. The commission was won by Rensaa and Minsos, who had set the stage for the decade with their exceptional design of the 1956 Ross Sheppard High School situated at the eastern edge of Coronation Park. The Edmonton Journal reported on September 12, 1962, that “Grey- haired Fred Minsos had never designed an airport terminal but he put in his bid to the federal government for construction of Edmonton’s International air terminal just the same. And in no time, Ottawa was on the phone. Rensaa and Minsos, Edmonton architects, had been awarded the $10,000,000 contract. That was the start of what promises to be one of the most modern, streamlined air terminals in the world.” The 950 foot long terminal was designed for the anticipated 1972 traffic load, which was considered very progressive in its time.

Peter Hemingway, an architect trained in England, who initially worked for Alberta Public Works, formed a partnership with colleague Charles Laubenthal and set up practice in the late 1950s. Their first commissions were modest and included prestigious residences such as the 1957 Shoctor House and the 1958 Lieberman House (both on Valleyview Drive), the 1958 Westmount Presbyterian Church at 13820 – 109A Avenue and the 1958 Gold Bar Baptist Church at 4725 – 106 Avenue. Their partnership was crowned with the wonderful Central Pentacostal Tabernacle at 116 Street and 107 Avenue, the first of two signature

buildings on this site. Charles Laubenthal moved to Ottawa later in the decade and Peter Hemingway became one of Edmonton’s preeminent architects of the period with his award-winning 1967 Coronation Pool (now the Peter Hemingway Leisure and Fitness Centre in Coronation Park) and the 1967 Stanley Building on the Kingsway at 118 Street. In 1972, Hemingway designed the second of two Central Pentacostal Buildings, which would be the first of his iconic pyramidal structures that have come to symbolize the city. The building was demolished in 2007.

Architects Donald Bittorf and James B. Wensley founded an important practice in 1964. Bittorf was a 1954 graduate of the University of Washington in Seattle and a 1955 graduate of the Harvard Graduate School of Design. His early professional experience was

with Dewar Stevenson Stanley in the 1950s. Wensley, a 1956 graduate of the University of British Columbia School of Architecture, was influenced by the work of West Coast practitioners, as was Bittorf. In 1964, Bittorf and Wensley founded a partnership and produced the airy 1967 pavilions in Mayfair Park (now Hawrelak Park) and the elegant 1968 residence for John and Barbara Poole at 7320 – 158 Street, an exquisite example of West Coast Modernism. Wensley’s 1966 residence for himself is also a brilliant rendition of the West Coast Post and Beam Style influence.

Bittorf and Wensley also designed a new building for The Edmonton Art Gallery, which was completed in 1969. From Modern Architecture in Alberta, published in 1987, author Trevor Boddy writes: “Edmonton Architect Don Bittorf designed a superb low-key art gallery that uses Brutalist elements in a surprisingly warm and humane manner. The understatement of The Edmonton Art Gallery is in direct contrast to the braggadocio of the Boston City Hall-inspired looming forms of the Alberta Court House behind it, the two forming a set-piece on Brutalism in architecture. Both the colour and board-forming of the concrete of the art gallery soften this building, which might have appeared like a squat bunker had it not been so carefully detailed. The sky-lit great staircase of the gallery is one of the most handsome spaces of any building in the province.” This outstanding building was the culmination of their creative partnership, which ended in the early 1970s. The long-lasting firm of Blakey, Blakey and Ascher came to an end in the early 1960s with the untimely death of Rudolph Aschher. William and Richard Blakey had been among the province’s longest practicing architects. their work spanning the styles of the century and convincingly embracing the Modern movement. The firm’s assets were purchased by Robert F. Bouey who had worked in the office since 1951. In 1962, Robert and his brother Howard Bouey (from McKernan and Bouey), formed the partnership Howard and Robert Bouey Architects. Among their early commissions were numerous churches, some of the best at the time for their modern expressionism, including Chalmers United at 12312 – 132 Avenue, Braemar Baptist 7407 – 98 Avenue, Kirk United 13535 – 122 Avenue, Grace United 6215 – 104 Avenue, Trinity United 8810 Meadowlark Road and the structurally expressive St. Stephens United at 10115 – 79 Street in Forest Heights.

In the 1960s, CN was taking an active interest in the development of Edmonton’s civic centre and decided to undertake the building of one of the proposed high rise office towers. A call for the design of a new train station and tower was prepared and the submission from Allied Development Corporation, a group of Alberta businessmen, was chosen. The agreement arranged for a 99-year lease to Allied, who would demolish the old terminal, build and own the proposed tower, and rent seven floors to CN. The building housed CN’s railway terminal on the lower floor, while most of the rest of the building was leased as office space. The main tenants in the newly opened building were Canadian National Enterprises and the health, welfare and telephone departments of the City of Edmonton. The 26-storey CN tower, designed by Calgary architects Abugov and Sunderland, opened on February 14, 1966, and was described as Canada’s tallest office building west of Toronto. It was an imposing landmark, the first of a series of major high rises that were to define Edmonton’s downtown skyline. High-rise development escalated following the Tower’s construction. Abugov and Sunderland established an office in Edmonton office and went on to design many commercial buildings in the city over the following decades, including the mammoth West Edmonton Mall.

Alberta Public Works

Top to bottom: U of A Education Building (Provincial Archives of Alberta WS.32.1), Downtown in the mid-19.0s (Edmonton Archives EA-10-2.95)

Alberta Public Works (APW) designed many significant buildings in the post-war period, including most of the government and University of Alberta buildings at the time. Having been established in 1908, the history of APW is long and complex and worthy of a separate study. Ronald C. Clarke came to APW in 1952 from the office of Patrick Campbell-Hope. He was appointed Chief Architect on January 1,1954, and served in that capacity until the August 31,1958. Clarke was responsible for the Jubilee Auditoria in Edmonton and Calgary that opened in 1955. He also designed the Department of Public Works Building 1 on the Legislature grounds, the Alberta Research Council Building on 87th Avenue and 114th Street (now demolished), the School for the Deaf (with Nick Stroich, Architect) and the Mental Health Buildings at Alberta Hospital in north Edmonton. Clarke was also responsible for the Intern.s Residence at the University of Alberta Hospital. At this time, the Department completed the U of A Physics and Chemistry Buildings and the Administration Building.

Alberta Public Works grew under the leadership of Arthur Arnold, P.Eng. He was Superintendent of Buildings in 1946 and Deputy Minister from 1954 to 1964. At its high point, APW had a total of 180 staff and Arnold was very proud to say that .it was the largest architectural office west of Toronto.. In the post-war period, APW nourished many young architects who stayed with them or went on to establish their own firms, including: Bryan Campbell-Hope, son of architect Patrick Campbell-Hope.

Architect G. Douglas Menzies was responsible for the design of the Physical Education Buildings at the U of A, as well as the three Student Residences and the award-winning Food Centre at Lister Hall. Another of his major projects was the 1967 Provincial Museum & Archives in Edmonton’s Glenora neighbourhood and the Terrace Building, which housed the Alberta Treasury and other departments. The Red Deer Provincial Building was an important structure designed by Edmonton architects Freda & Dennis O’Conner and Ron Maltby, who also designed the progressive Michener Centre at the U of A Farm with its innovative Married Students Housing building.

In the late 1950s, the Alberta Government began planning the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology (NAIT) to be located adjacent to the Municipal Airport. The Alberta Pubic Works Architect’s Office was responsible for the project and the design was headed up by George Jellinek, who later joined the firm Richards and Berretti. Due to the immediate need for the facility, the project was an example of fast-track design and construction. The original site planning and building design are, perhaps, the purest example in Edmonton of the 1940’s International Style that is exemplified by the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago designed by Mies van der Rohe.

The 1960s Close With International Recognition

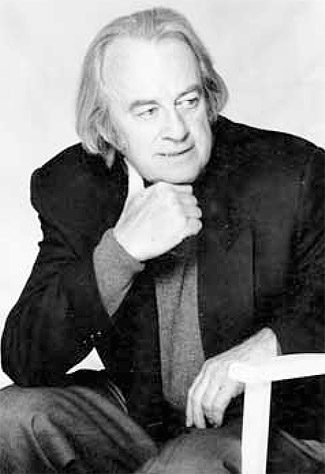

Top to bottom: 19.7 Students. Union Building Stair Detail (H.J. (Bertie) Richards), 194. Students. Union Building (now University Hall)

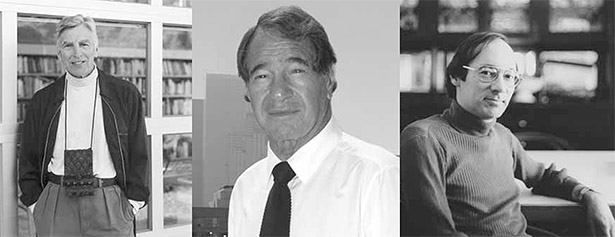

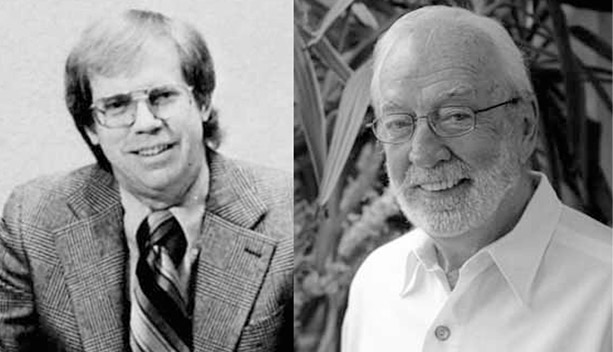

By the mid-1960s, the Students’ Union at the University of Alberta had outgrown its home and a new facility was planned for construction across the street. The new Students’ Union building, designed by Richards Berretti and Jellinek, opened in the fall of 1967 and was a large, dramatic example of the International Style. The building utilizes the typical International Style tower and podium design, with exposed concrete structure, pre-cast cladding and a simple composition of volumes. The interior detailing features sculpted and expressive open wood stair treads on exposed steel supports, raw concrete column finishes and custom designed ceiling grid light fixtures that were clearly articulated in the structure. The University of Alberta’s Housing Union Building (HUB) on the alignment of 112 Street between 88 Avenue and Saskatchewan Drive was conceived and constructed between 1968 and 1973, in a time of great student expansion at the University of Alberta, and much student unrest around the world. HUB was planned by the Students’ Union Housing Commission, with the support and cooperation of the University, in response to a serious shortage of student housing. Preliminary feasibility studies had been completed showing that an apartment- style residence containing convenient retail services, located on campus would be financially viable. The University Board of Governors gave their approval in principle to proceed to architectural drawings and cost estimates. At this time, the Toronto architectural firm Diamond and Myers (Jack Diamond and Barton Myers had both apprenticed with acclaimed American architect Louis Kahn in Philadelphia) were just completing a new and imaginative long range campus plan for the U of A, they welcomed the opportunity, along with Edmonton architect Richard L. Wilkin, to design a prototypical building that would illustrate a major plan concept . that housing and other ancillary service buildings could be constructed in such a way as to provide weather-proof links between academic structures. Such links were to be above ground and would therefore benefit from natural light and colour while providing protection from the winter weather. John Morris Dixon writes in the Progressive Architecture February 1974, “In a bravura demonstration of their own long-range plan for the University of Alberta campus at Edmonton, Diamond and Myers have created a prototype cold-climate community. They have lined up shops and apartments along a climate-controlled galleria and placed them all above the sheltered service roadway. By means of a 950 foot long skylight they have made the most of the sub-arctic sunlight, drawing it in to shimmer over glassy walls and bounce off bright shutters and posters in a visible expression of student vitality… The housing is exceptional not only for its precedent-shattering design, but for its sponsorship by the students themselves.”

The Housing Union Building is an icon of modern architecture in Alberta, having been published extensively in the world’s architectural publications over the years, including Global Architecture Special Issue 1970-1980 (1980), Progressive Architecture (February 1974) and Architectural Review (May 1980) to name a few. Although there have been numerous changes and modifications over the years since its completion, it retains its original character and remains Edmonton’s most recognized building in the eyes of the international architectural community.

Déja Vu

The post-war period was an important time of growth and maturation for the Edmonton architectural community. Alberta’s oil-driven economy started in 1947 and fueled tremendous growth and opportunity. On February 7, 1950, The Edmonton Journal reported that .Edmonton this year may expect a construction program totaling at least $90,000,000, a survey revealed Tuesday. The survey indicated that the greatest per capita construction pace on the North American continent will be established here in 1950.. This story of economic boom has been repeated several times in the ensuing 60 years since the Leduc oil discovery of 1947. The opportunities that were offered to post- war architects produced many fine buildings and some have been recognized and protected. The Jubilee Auditorium and the Peter

Hemingway Fitness and Leisure Centre in Coronation Park stand as grand examples of this. Unfortunately, in the name of progress, others have been lost: Central Pentacostal Tabernacle Buildings by Peter Hemingway and Charles Laubenthal and the soon-to-be-replaced Edmonton Art Gallery by Don Bittorf and Jim Wensley. Many more post-war buildings are potentially in danger. As can be expected, there is general lack of information about and understanding of our post-war building heritage. In the pubic minds’ eye these structures are not considered historic, although convention dictates that buildings older than 50 years deserve historic status. Although progress will always be a force with which to contend, a mature Edmonton will recognize that our future identity must also include the impressive achievements of our Modernist architects and builders.

Left to right: Barton Myers (Barton Myers), Jack Diamond (Jack Diamond), Richard Wilkin (Richard Wilkin)

Bibliography & Sources

1. ARCHIVAL SOURCES

Alberta Community Development, Historic Sites Service

City of Edmonton Archives

Glenbow-Alberta Institute Archives

Provincial Archives of Alberta

University of Alberta Archives

University of Calgary, Canadian Architectural Archives

Edmonton Public School Archives

2. CONTACTS AND INTERVIEWS

James ‘Joc’ Bell, Edmonton

Donald Bittorf, Vancouver

The William Blakey Family

Robert and Howard Bouey, Vancouver Island

Bryan Campbell-Hope, Edmonton

Douglas Campbell, Edmonton

Maxwell Dewar Family

The Peter Hemingway Family

Nancy Lord, Edmonton

John A. MacDonald, Edmonton

The Neil McKernan Family

Barton Myers, Los Angeles

John and Barbara Poole, Edmonton

Bertie Richards, West Vancouver

Beverly Seaman, Edmonton

James Wensley, Vancouver

Richard L. Wilkin, Edmonton

Bernard Wood, Edmonton

3. PROFESSIONAL JOURNALS AND NEWSPAPERS

Journal of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada

The Canadian Architect

Edmonton Bulletin, Architecture and home building features, 1936-1953

Edmonton Journal, Architecture and home building features, 1936-1960

SSAC Journal

4. PUBLISHED STUDIES, SOURCES AND THESES

Boddy, Trevor, Modern Architecture in Alberta. [Regina: Alberta Culture and Multiculturalism, and the Canadian Plains Research Centre, 1987].

Bronson, Susan D., and Jester, Thomas C., eds. Mending the Modern. Special Issue – APT Bulletin. 23:4 [1997].

Cashman, Tony, and Croll, Norman H., 50 Years in Architecture A History published by Schmidt

Feldberg Croll Henderson to mark the 50th Anniversary of the Firm founded in 1938 as Rule Wynn and Rule. [Edmonton: Schmidt Feldman Croll Henderson, 1988].

Fedori, Marianne and Tingley, Ken and Murray, David, The Practice of Post-war Architecture in Edmonton, Alberta – An Overview of the Modern Movement, 1936-1960 [2001.

Dominey, Erna, “Wallbridge and Imrie The Architectural Practice of Two Edmonton Women, 1950-1979”, SSAC Bulletin [Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada] 17:1.

Frampton, Kenneth, Modern Architecture. [Douglas & McIntyre, 1992].

Luxton, Donald The Modern Architecture of North Vancouver 1930-1965 [no date]

Luxton, Donald and Vidners, Valda The West Vancouver Survey of Significant Architecture 1945-1975 [no date]

Maitland, Leslie, Hucker, Jacqueline, and Ricketts, Shannon, A Guide to Canadian Architectural Styles. [Broadview Press].

Murray, David, Tingley, Ken Fedori, Marianne and Luxton, Don, An Inventory of Modern Architecture prepared for the City of Edmonton Planning Department 2007

Wetherall, Donald and Kmet, Irene, Homes in Alberta: Building Trends and Design 1870-1967. [Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1991]

Wetherall, Donald, Architecture, Town Planning and Community, Selected Writings and Public Talks by Cecil Burgess, 1909-1946 [Edmonton: University of Alberta Press. 2005.

Walter J. Phillips, Dawn, Edmonton Airport, 1942, 1942 (Art Gallery of Alberta Collection, gift of J. A. Imrie, Dr. Orr and Mrs. H.R. Milner, 1943)

2 Comments