EDMONTON’S SUBURBAN EXPLOSION 1947-1969

Troy Smith

2007

Today, the City of Edmonton has one of the lowest population densities of any city in Canada. At a miniscule 4.33 people/acre we are by far the largest consumers of land not only in Alberta but all of Western Canada. With a population of 730,372 the City of Edmonton encompass a land mass of 684.37 square kilometres.1 Edmonton’s population density is lower than other sprawling Canadian cities such as Calgary

(5.3 people/acre), Winnipeg (5.5 people/acre), Regina (6.1 people/acre) and Saskatoon (5.2 people/acre). Edmonton’s footprint is actually greater than such ‘big’ cities as Toronto, Montreal, Philadelphia and Chicago, even though these cities have two to three times the population. So how did our city get to this point? The boom years, beginning with the end of the World War II in 1945 and the 1947 major oil discovery in Leduc, Alberta, created an ideal setting for the suburban growth that would prove to change the shape of Edmonton forever.

BEGINNINGS

In the 1940s, Canada was dealing with two cultural conditions, the after effects of the previous decade’s depression and the massive influx of servicemen and women returning home from the war. Some economists of the era warned that the end of World War II artificially ended the depression and that the country would slip back into economic decline. Within Alberta these doomsday predictions proved to be completely off the mark due two factors: first, the discovery of oil at Leduc in 1947 and second, the massive housing shortage created by returning war veterans and the subsequent marriage/baby boom. At the start of the 1940s Edmonton’s population was 91,723 while at the close of the decade in 1950 the population had increased by 62% to a total of 148,861.

With the unprecedented population increase and the new found prosperity provided by the oil industry, the city was faced with a dire need to expand. The existing urban patterns of Edmonton had not changed significantly since the 1920si many secondary roads were still covered in gravel and the city’s housing stock was deteriorating due to a lack of maintenance throughout the depression and war years. In fact, neighborhoods that had been planned in the 1920s remained largely empty until this boom, providing a blank canvas for new development.

SUBURBAN GROWTH

The majority of this blank canvas was filled with suburban development. Cheap agricultura land was plentiful, allowing developers and home builders to purchase parcels by the acre in order to build new affordable single family houses for the exploding Edmonton population. In looking back, it is clear that development in this period was significantly different from that preceding the post-war boom. There are four main factors that led to this new type of suburban growth: limited availability of existing good-quality housing, low housing costs, government subsidies for road construction given the rise of the automobile, and the beginning of a markedly different consumer culture.

A primary factor contributing to suburban growth was the need for quality housing. At the time, the City of Edmonton and the Province of Alberta were leading the country in the sharp increase of both marriage and birth rates and the housing supply could not keep pace. The number of households in Edmonton increased significantly in a very short period of time and the existing housing stock could not meet this incredible rise in demand. The extreme shortage of housing prompted the contemplation 1940s – 50s housing under construction of rather radical temporary solutions, “in November 1948 the city actually considered allowing construction of 12-by-22-foot temporary garage- like shelters.”3 The other alternative was to purchase a house in the suburbs. Suburban development was clearly needed to address the number of people flooding into the city.

The speed at which housing was developed meant that essential services could not be guaranteed – a fact that was off-set with lower sale prices and annual property taxes. These incentives further increased the desirability of this new housing stock. As these newly developed lands were previously agricultural, there were no existing services and the City of Edmonton faced pressure to keep infrastructure expansion in time with the rapid pace of suburban development. This was a losing battle as road construction and services such as sewer, power and water very quickly fell behind housing construction. As a result, housing and property taxes were lowered to compensate for the lack of local fire and police services and schools. Understandably, the provision of services became an important political issue. In 1951, $25 million of the provincial budget was allocated to local municipalities for infrastructure and road construction alone.2

The availability of government subsidies for new road construction also contributed to suburban growth. Across North America, a new car culture was taking hold and with it the desire and expectation that every family would own an automobile. “Between 1945 and 1951 vehicle registrations almost doubled in the province, rising from 130,000 to more than 250,000.”4 The desire for cars created the need for freeways, which ultimately allowed people to travel much larger distances, eliminating the need to live centrally. The rapidly expanding and affordable suburbs made even more sense.

Finally, a new form of consumer culture was taking hold and marketing campaigns aggressively targeted the middle class family with the “North American Dream” – a new car parked in the driveway of their new house. The comparison of this image to the dilapidated early 20th century housing stock in Edmonton only strengthened the position of the suburban home as the top choice. The search for the dream home was on. The ideal family – with an income generating working father and a stay-at-home mother -began to buy into this new material culture focused on improving the family’s well being. Household appliances such as the toaster, blender, electric range and television were intended to give people more time for leisure activities freeing them from mundane household chores. Even leisure activities began to take on a consumerist nature -in 1952, the Paramount Theatre opened with 1,500 seats in a fully air-conditioned environment. Edmonton was truly a modern city.

NEIGHBORHOOD PLANNING

With the flood of families purchasing housing in the suburbs the Planning Department began to fill a vital roll in the development of the city. Many large tracks of undeveloped land were owned by the City due to the foreclosures that were common in the real estate collapse of the early 1900s. The Planning Department was able to control the development of many neighborhoods from initial conception through to final sale. In 1949, Noel Dant was hired as the first Head of the City of Edmonton Planning Department. Dant was born in England in 1914 but moved to the United States to pursue higher education in town planning and architecture at both Harvard and Yale Universities. The timing of his arrival in Edmonton was ideal in terms of his ability to influence the form and maturation of the city in the coming decades.

Dant brought the concept of the ‘neighborhood unit’ to Edmonton. The neighborhood unit was commonly taught in planning schools throughout North America at this time, but had not yet been put into conventional planning practice. From the beginning of the 1900s through to the late 1940s, Edmonton was planned on a conventional street grid with uniform and rectilinear blocks and streets (illustrated by communities such as Inglewood and Westmount). Many criticized this system as sterile and unattractive as well as unresponsive to the existing topography of the land to which the grid was applied. The uniform street grid also allowed the abundance of new automobile owners to short-cut through residential communities in an attempt to avoid the increasing traffic congestion instead of staying on the main arterial roads. Dant’s neighborhood unit attempted to address all of these concerns.

Homes in Alberta (Edmonton: The University of Alberta Press/Alberta Culture and Multiculturalism/Alberta Municipal Affairs, 1991)

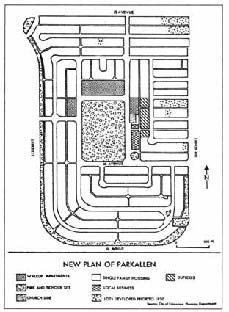

In 1951, the first community planned by Dant, Parkallen, was approved. Dant’s vision for Parkallen was to modify the street grid in such a way as to allow a visitor to the community to easily navigate to a destination while making it difficult for the unwanted commuter looking for an easy short-cut from one major street to another.

At the literal centre of Dant’s neighborhood unit is a major green space associated with a school or public park. Surrounding the central green space, higher density residential apartments and townhouses are located next to community-oriented businesses and typically a church. The remainder of the community is composed of single family houses and, in some cases, additional commercial businesses at the outer edges of the community. Dant’s neighborhood design ensured that all neighborhoods would have the following characteristics, as noted in Clarence Perry’s 1939 planning handbook, Housing in the Machine Age:

- Enough density to support a school at the centre of the community.

- Clear boundaries that provide the neighborhood with an identity and legibility.

- The heart of the neighborhood made-up of community oriented facilities, such as schools, parks and community centres that the residents can take pride in and are able to walk to.

- The neighborhood would be provided with a public green space for recreation and attractiveness.

- Convenient shopping facilities should be provided but not necessarily at the centre of the community in order to discourage outside automobile traffic from entering the community.

- The curvilinear street pattern enables the local traffic to be directed in and out of the neighborhood efficiently while discouraging outside traffic from short cutting through.

Throughout the 1950s approximately 40 such neighborhoods (including Sherbrooke, Glenora and Strathearn) were built in Edmonton based upon Dant’s unit plan. The neighborhood designs became increasingly less rectilinear in the early 1960s, culminating in communities such as Lendrum. The neighborhood unit was modified extensively and taken to an extreme scale with communities in the19 60s and 1970s such as West Jasper Place and Millwoods. These designs were made up of a series of super blocks complete with housing clustered on the margins in short cul-de-sacs. These neighborhoods can be seen as the model for the typical suburban development of today.

THE SHOPPING MALL

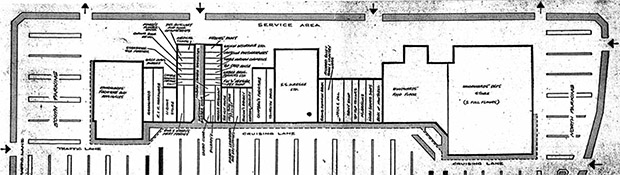

Major roadways were constructed bounding communities such as Parkallen and Glenora that enabled the daily commute of the suburban resident to the downtown. A new phenomenon began to develop along the major roadways that would influence the form of the city to this day – the shopping mall. The ‘malling’ of Edmonton began with the construction of the Westmount Shoppers’ Park along Groat Road and 111 Avenue in August of 1955. Built for the sum of $5 million, Westmount Shoppers’ Park originally covered six city blocks with 40 shops including Woodward’s and Kresge department stores. The mall was surrounded by asphalt parking for 3,000 cars and was the largest paved area in the province at the time, other than the major airports.

At the time, the Westmount Shoppers’ Park was described as the ultimate one-stop shopping destination, “designed for the shopping convenience of the Edmonton housewife and featur[ing] outlets for almost every type of merchandise or service available in the city.”5 An ad describes one of the feature amenities of the original Shoppers’ Park: “Avoid traffic congestion, eliminate parking problems. There’s always plenty of free parking space right on the premises.”6

Westmount Shoppers’ Park, and other malls that followed, came to symbolize the 1950s notion of progressi progress was jumping in your brand new Chevrolet, driving to the mall to park in a sea of asphalt, enabling the purchase of household goods that every progressive 1950s family needed.

“As cities have grown in population, consumer demand has been decentralized, and as personal mobility has increased through the great growth in car ownership, the number of shopping centres has also increased.”7 In Edmonton this statement proves abundantly true. From 1955 to 1970, seven regional shopping malls were constructed in Edmonton: Westmount (1955), Bonnie Doon (1958), Meadowlark Park (1963), Northgate (1965), Capilano Plaza (1966), Centennial Village (1967) and Southgate (1970).

The population of Edmonton in 1970 was 429,750 and using the common guideline of 100,000/mall (the population required to support a regional shopping mall) the Edmonton shopping scene in 1970 was fully saturated. In fact, if the downtown could be viewed as another regional shopping mall it became the eighth centre and also required 100,000 people to support it. The downtown at this time was lagging behind Westmount and Bonnie Doon as a shopping destination, as it was perceived to be less convenient. This era marked the downturn for Edmonton’s downtown, and with the construction of West Edmonton Mall, the decay was only furthered.

The suburban explosion associated with the 1950s Alberta population and economic boom has impacted the city in both negative and positive ways. From a negative perspective we are still living within a ‘malled’ city, although the shape of the mall has evolved into the ‘Power Centre’ (a collection of big ‘box’ stores surrounded by a sea of parking).

Both the suburban mall and the power centre are car oriented environments where you can supposedly fulfill all of your consumer needs. The scale of each is completely different, however. Within the power centre everything is oversized including the stores and the parking lots, and the scale of the pedestrian is completely lost. As a comparison, the South Edmonton Common power centre is spread over 320 acres whereas Westmount Shoppers’ Park was only 30 acres when originally constructed. Similar to the mall, the power centre is the anchor around which many suburban developments today are constructed -not unlike the Westmount Shoppers’ Park or Bonnie Doon Shopping Centre of 50 years ago. And although car oriented convenience is the goal, it has become clearly evident that power centres create more traffic issues than they solve.

Continuing the trend of bigger is better are the suburban residential developments of today. Contemporary suburban communities are a far cry from the neighborhood unit designed by Noel Dant in the early 1950s. Dant’s communities promoted walking, green space, close proximity of services and heterogeneity. Today’s suburban developments promote the automobile, tiny ill-used front and rear yards, commuting to school or work and homogeneity. Ferenc Mate in his book, A Reasonable Life, states: “(Suburbs) do nothing to satisfy our social human needsi they do nothing to encourage us to be anything but strangers who happen to park their cars on the same street every night.”8 The goal of creating better communities appears to have sacrificed social connection for personal commodity.

Although the negatives are easily tabulated, there are also positive legacies from the rapid development during the early 20th Century economic boom. Firstly, the ‘Dant’ neighborhoods developed during that time offer a rich housing stock, with large landscaped lots, mature trees, a fully developed service infrastructure (sewer, roads, parks, fire, police, schools), a variety of housing types and options for commuting including walking or transit. These previously suburban neighborhoods, which are now often described as urban or inner city, offer alternatives and choices to the current homogenized suburban housing stock.

Secondly and most importantly, the legacy of suburbanization has forced a re-awakening to the quality of our urban and suburban environments and the aspects of good community design. The popularity of groups and programs such as Active Edmonton, Go for Green and Walkable Edmonton are indications that people are tired of depending solely on cars and desire choices in how they move from place to place and integrate an active lifestyle into everyday living. Perhaps this age will become known as the conclusion of suburbia and the rebirth of livability.

ENDNOTES

1. Statistics Canada, 2006 Community Profiles, Edmonton↩

2. “Municipal Aid a Budget Feature”, Lethbridge Herald, 6 March 1951, pg. 1.↩

3. Maunder, Mike. “A new urbanworld appears as suburbia transforms cities.” In Alberta in the 20th Century: Volume I. (Edmonton, United Western Communication Ltd., 2001), pg. 210.↩

4. Payne, Michael, Wetherell, Donald, Cavanaugh, Catherine, ed. Alberta Formed Alberta Transform (Edmonton/Calgary: University of Alberta and University of Calgary Presses, 2006), pg. 575.↩

5. “$5,000,000 Shoppers Park Opens”, Edmonton Journal, 17 August 1955, section 4, 1.↩

6. “Westmount at 50,” Real Estate Weekly, vol.23 no.35, 01 September 2005.↩

7. Brown, Sheila. “Shopper Attitudes Towards Competitive Regional Centres as a Factor in Patronage Choice.” In Smith, PJ, ed. Edmonton: The Emerging Metropolitan Pattern: Western Geographical Series No.15 (Victoria, University of Victoria, 1978), 94.↩

8. http://theslowhome.com/blog/getinformed/↩